As approved by the Board of Governors in its meeting held on the 17th April, 2023 the following Position Statement Investing in the Well-Being of Students, Staff and Faculty

Outline

- The situation of youth in MLCU and elsewhere

- Deaths of despair

- Setting out on this journey in MLCU

- Mental health is communal

- Work-life balance for faculty and staff

- How to make the most of university: for students

- Factors affecting length and quality of life

- Recommendations

- Steps so far

This topic has immediacy and urgency. Investment in well-being will reap short-term and long-term dividends in individual, university and societal transformation.

The Situation of Youth in MLCU and Elsewhere

- During the Covid pandemic lockdown the office of the Dean of Students conducted a survey of 897 online MLCU students from 11 departments in Dec 2020. Of these

- 87% expressed feelings of stress, 36% of them experienced stress ‘once a week’ or ‘nearly daily’. The main stressors were uncertainty about the future especially higher studies, job prospects and financial security.

- Academic stress was experienced ‘sometimes’ or ‘often’ by 74% of students. More than half (55%) said that academic motivation had decreased.

- Emotional instability, demonstrated by feelings of ‘nervousness’, ‘anxiety’, ‘easily irritable’, ‘loss of interest or pleasure in things’, ‘sleep problems’, ‘difficulty in concentration’, ‘feeling of failure’, ‘letting the family down’, was felt by 43 – 58% of students.

- Thoughts of self-harm occurred ‘sometimes’ to 14.5% (130 students) and ‘often’ to 2.5% (22 students).

- When asked if they were able to adjust and cope with the stress of the previous three months only 22% agreed.

- This small group used the following self-coping activities: try to work it out myself (63%), help from friends and family (61%), university teachers and counsellor (41%), distract with other things (43%), video games/movies (40%), more sleep (37%), gardening/cooking/baking (34%), arts/crafts (25%), prayer (22%), learning a musical instrument (18%)

- Willingness to speak to a counselor: 77% said no

- Quotes and comments

- “My life has no meaning because nothing in life is good”

- “I hate my family”

- “I feel like cutting myself. Gives me some kind of unknown pleasure”

- “I am always sad.”

- “I cannot focus on anything and I think I have anxiety disorder”

- “I get very angry whenever I’m not able to do my own work.”

- “This whole lockdown thing has been demotivating for me, I have no interest in doing anything”

No | Item | Dec 2020 (n=897) F564 M315 | Feb 2023 (n=687) F492 M195 |

| Feeling stressed | 87 | 88 |

| Frequency of stress: daily/ almost daily | 36 | 33 |

| Stress affecting studies: sometimes/often | 74 | 48 |

| Future studies | 31 | 32 |

| Future job | 35 | 45 |

| Financial | 32 | 37 |

| Personal | 33 | 34 |

| Negative feelings: ‘anxiety’, ‘easily irritable’, ‘loss of interest or pleasure in things’, ‘sleep problems’, ‘difficulty in concentration’, ‘feeling of failure’ | 43-58 | 22-34 |

| Self-harm | 2.5/14.5 | 2.6/15.0 |

| Inability to cope | 49 | 48 |

| Friends and family | 35 | 36 |

| Work on it myself | 46 | 45 |

| Mentor/teachers/counsellor | 15 | 17 |

| Get upset, vent out | 12 | 25 |

| Distract myself with other activities | 24 | 33 |

| Prayer, trust in God | 53 | 82 |

| Alcohol, drugs | 1 | 3 |

| Sleep more | 15 | 26 |

| Get away from mothers, be by myself | 14 | 29 |

| TV, video games, movies | 28 | 55 |

| Arts/crafts/DIY | 8 | 13 |

| Playing/learning a musical instrument | 10 | 13 |

| Gardening, cooking, baking | 27 | 42 |

Post Covid sense of loss: from a BSc psychology student

“I enrolled for a bachelor’s degree in psychology at Martin Luther Christian University in 2019. For that first year, everything was, dare I say, perfect; I was studying a subject that my heart was invested in, the university was the perfect ‘second home’ and I was faring very well in my classes. Then life threw me a curve ball – the Covid-19 pandemic. Two years of constant mask-wearing, social distancing and quarantine did a number on us all and I found myself in the unfamiliar territory of online zoom classes and virtual everything. This disrupted the flow of my learning greatly, as there is a world of difference between actually attending a class in person and attending one from the comfort of one’s sofa or bed. In my case, it proved to be quite the demotivator as I struggled with understanding the different concepts and branches of psychology in these two years. Having only attended a few months of offline classes before graduating, the victory of actually achieving the degree was laced with the feeling of dissatisfaction and confusion. What now?”

Wish to leave Meghalaya

Many students studying at colleges and universities in Bangalore, especially women, state very clearly that they do not want to return. The most common reason is that there are no career or financial prospects in Meghalaya. Most of them would prefer to go abroad, east and southeast Asia are beckoning destinations. Women students cite stifling family and societal expectations and the burdens that matriliny places on daughters.

The departure of youth from the Northeast has become a subject of literature, sociology and economics. In her collection of short stories Boats on Land, Janice Pariat, relates the troubled life of Barisha, a young Khasi woman who finds work in Delhi. In Leaving the Land, Dolly Kikon and Bengt Karlsson, describe the migration of women from the Northeast for affective labour in the Mainland and their emotional and economic experiences.

Stress among Gen Z

That stress, anxiety and depression has increased among Generation Z during the pandemic and after is well-documented. Merely returning to campus and some degree of normalcy has not assuaged the damage to well-being. Not only are there residual issues from Covid such as a dip in family finances, loss of social connections and the deprivation of studies, but the post-Covid world is fraught with uncertainty not only to their future wellbeing, but of threats to the planet, social justice and a stable world order. Even for the hopeful and idealistic, these are devastating perils. The death by suicide of one of our students on Mar 26, 2023 is despairingly illustrative of the current psychological and emotional state of the youth.

A WHO survey found that one-fifth (20.3%) of college students had 12-month DSM-IV classified mental disorders; 83.1% of these cases had onsets prior to beginning their higher education. Among men, substance disorders, and, among women, major depression were the most important. Only 16.4% of students with 12-month disorders received any healthcare treatment for their mental disorders, and many dropped out. Detection and effective treatment of these disorders early in the college career might reduce attrition and improve educational and psychosocial functioning.

Deaths of Despair

Is a term that has recently entered the lexicon of health professionals. Despair is defined as “a state of mind in which there is an entire want of hope. From a psychological perspective, this definition focuses on a cognitive state that includes defeat, guilt, worthlessness, learned helplessness, pessimism, and limited positive expectations for the future”. Deaths from despair are those that occur from suicide, drug overdose and alcoholism (specifically from liver failure)”. These deaths can occur in every demographic, but are related more to lower levels of education, poverty, rural areas, illicit drug use and negative thoughts and self-harm behaviours. The ‘precursors’ may not have high predictive value.

Neuroscience and behavioral sciences tell us that “It has been observed that human beings are constrained by evolutionary strategy (ie, huge brain, prolonged physical and emotional dependence, education beyond adolescence for professional skills, and extended adult learning) to require communal support at all stages of the life cycle. Without support, difficulties accumulate until there seems to be no way forward.”

Deaths of despair are anecdotally common among tribal communities and certainly in our society. Perhaps there is no family in this room that has experienced a ‘death of despair’, or have relatives, neighbours or friends that are vulnerable. Our University is a community of young adults, at high risk for these tragedies. All campuses the world over share this vulnerability. On Mar 2, 2023, IIT Bombay published an investigative report on the suicide of a dalit student. An article in The Hindu by two former IITians commented that “The buoyancy of youth is not equal for everyone.”

Setting Out on this Journey in MLCU

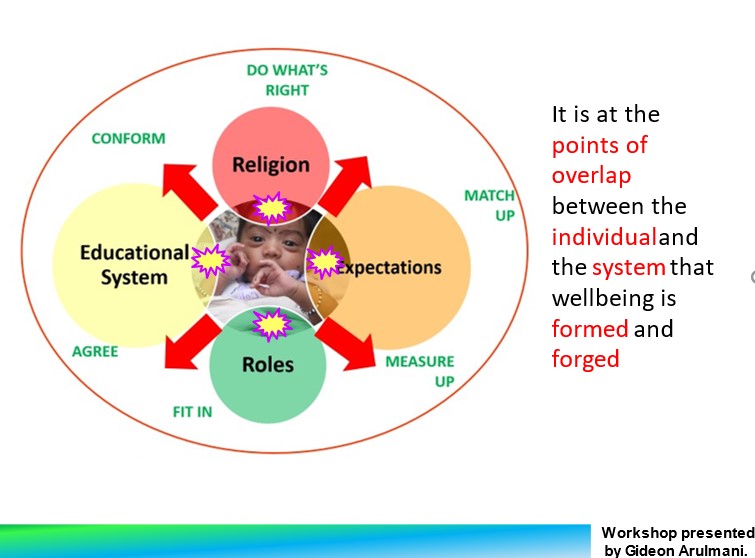

Our deliberations and initiatives began with the MLCU Retreat on Aug 1-2, 2022. Dr Gideon Arulmani introduced the topic to us with a presentation entitled, “Wellness and its (Dis)contents!”. Some insightful nuggets were:

- Wellness lies at the heart of mental health and emotional well-being. It’s become a trendy buzzword today, but what is it actually about, satisfaction, happiness, contentment and enjoyment? Equanimity is another word, satisfaction with the status quo. Some philosophical and spiritual non-linear views are expressed in different cultures as, sotopanna (Buddhist), eudaimonia (Aristotle), dharma (Indian), and Ikigai (Japanese) which emphasizes “human flourishing”, and “living correctly” and on finding meaning through the realisation of the self as it manifests within one’s context.

- There may be two views about happiness. One focuses on the self and the other focuses on the self in the community. It’s very much associated with finding relationships, building these connections of love.

- This is what the psychologist would tell you about well-being. In terms of definitions, it’s the person’s cognitive component, ie., thoughts and opinions about one’s life and the affective component ie., feelings and emotions about one’s life.

- Perceptions of wellness and work have been altered by Covid. And during this great rethink there have been pandemic epiphanies where people have been able to sit down and rethink.

- The pace and velocity at which change is happening is very, very rapid. One way to keep pace with change, is to say this is the kind of person that I am. This could be based on values, religion, lifestyle preferences. Social networks are important, perhaps among more tribals these networks are already in place.

- Gideon laid out 5 principles:

Principle 1 Development as a Spiral

- Development is not merely achievement of mastery over age-specific developmental tasks. It is a collection of overlapping movements; a continuous elaboration and construction, characterised by adaptation, discovery and renewal.

- May not necessarily always point in the ‘forward’ direction.

- May require the individual to return to earlier learnings, it may also require the individual to let go of earlier positions and begin anew.

Principle 2 Assess Before You Accept

- Practice restraint, flexibility and self-mediation.

- Does this mean the individual must live like an ascetic? Are malls places of evil temptations?

- It means building the ability to discern, to weigh up advantages and disadvantages and then accept, or let go.

- Support the individual to shape the future through actions executed thoughtfully and willfully in the present.

- Wellbeing does not emerge unbidden. Wellbeing is constructed in the crucible of actions executed thoughtfully, willfully and with control.

- Assessment and acceptance require: decision making skills, trajectory projection skills, and inoculation against failure

Principle 3 The Changing and the Unchanged

Wellness requires the individual to embrace change and transformation. It also requires the individual to consider this necessity from the essentially unchanging core of one’s self. It can be facilitated by:

- Diary/journal writing skills

- Exercises to identify what is relatively unchanging withing oneself

- Livelihood planning

Principle 4 Sensitivity to the Other

- Is there such a state as “personal” wellbeing? Can wellbeing exist independent of the others around us?

- Sensitivity to the “other” seems to be a value that characterises most tribal and indigenous cultures.

- Wellness calls for an engagement with life that is reciprocally caring, nourishing rather than manipulative; contributing and at the same time receiving.

- It can be worked out with exercises: to identify the networks one is a part of, to discuss the “why” of community projects, and to work out a giving and receiving balance sheet.

Mental health is Communal

In a treatise on Confucius and other Chinese philosophers, Alexus McLeodis in Psyche (2023) says that Asians have always known that mental illness is a communal phenomenon.

“Mental illness is often thought to be a matter of individual disorder. Modern psychiatry looks to features of individual experience, behaviour and thoughts to diagnose mental illness, and focuses on individual remedies to treat it. If you are depressed, this is understood as your response to circumstances, based on features of your genetics, disordered patterns of thinking, or personal problems and emotional states. Western treatment of mental illness follows these same individualistic lines. The individual is provided with medicine and therapy, which are sometimes helpful.

But such an emphasis on the individual can lead us to neglect communal approaches to treatment. Often overlooked are the ways in which social norms, cultural beliefs and communal attitudes contribute to mental illness. Chinese philosophy has long known that mental health is communal.

Features of the communities and cultures of which one is a member have great influence on the formation and expression of our emotions. It would be wrong to see anger, for example, as a universally natural response to certain events, independent of culture. Members of certain communities will be more likely to display or feel anger in given situations than members of other communities with different cultural norms governing emotion.

Mental illness is often due to a combination of genetic predisposition and situational features. What calls for anxiety, anger, joy or other responses will almost always be in large part dependent on communal norms, of the kind integrated into the expectations and behavioural tendencies of individuals from a young age, through interaction with the community. This is why, for example, disrespect of a parent or elder will cause enormous shame in certain Asian cultures, but not in many Western cultures. Cultural factors also make certain groups, such as Asians, less likely to seek psychiatric healthcare than other ethnic groups in the US.

There is evidence that mental illness is increasing in younger members of society, along with increases in suicide and attempted suicide. Such increases in mental illness might say less about individual traits than they do about certain alienating and corrosive features of our society. As Confucius himself said: ‘The faults of an individual are in each case attributable to their group.’ While many efforts, including providing greater access to professional mental health treatment, should be part of our response to the problem of mental illness, we should also carefully and seriously consider which aspects of our shared cultures might be contributing to the rise of mental illness.”

Work-Life Balance for Faculty and Staff

One study has shown that 84% of teachers stated that teaching is more stressful than before the pandemic, citing tougher work, struggles to engage students, and fears about self and family health.

More than half do not speak to anyone at work about their mental health. Job-related stress is twice as high among teachers and depression, three times as high as the general adult population.

The pandemic has altered perceptions of work-life balance, with the quality of personal, family and social life being considered more important than before. But to simply say that we’d be happier if we didn’t need to work or work for fewer hours is to miss the point. Why we work is a key question, apart from how much we work. “Work is consistently and positively related to our wellbeing and constitutes a large part of our identity. Ask yourself who you are, and very soon you’ll resort to describing what you do for work. Being busy contributes to happiness even when you think you’d prefer to be idle. Animals seem to get this instinctively: in experiments, most would rather work for food than get it for free.”

Gideon spoke of eudaimonic happiness: “The idea that work, or putting effort into tasks, contributes to our general wellbeing is closely related to the psychological concept of eudaimonic happiness. This is the sort of happiness that we derive from optimal functioning and realising our potential. Research has shown that work and effort is central to eudaimonic happiness, explaining the satisfaction and pride you feel on completing a grueling task.” This answers to some extent the question of whether working well results in better well-being, or whether those who already have a sense of well-being bring better performance to the workplace. A large-scale study found that well-being predicts outstanding job performance (MIT Sloan Management Review, 2022)

But there are different approaches in life. An international study found that about half of individuals in all surveyed countries preferred hedonic happiness. About 13% choose to pursue a combination of enjoyment and fulfillment, preferring a rich and diverse experiential life. The psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi says that artists and other professionals feel happiest when their “body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile.”

A good work culture is characterized by clarity of organizational goals, to which employee expectations are clearly aligned. With expectations, guidance and support need to be provided as part of systems and processes. Staff need clarity on which behaviours result in promotion and job security. Officers must be held accountable to outcomes (HBR, 2018).

How to Make the Most of University: for students

In an article by this title a young psychology lecturer, Nic Hooper, sets out a sensible and practical approach for students to learn “psychological flexibility as the key to coping with difficult times and to pursuing what really matters to you”.

He recommends the six ways to wellbeing (New Economics Foundation and Institute for Positive Psychology and Education)

- Challenge yourself.

- Connect with others.

- Give to others.

- Self-care.

- Embrace the moment.

In his work with students, he uses “an approach called acceptance and commitment therapy (commonly called ACT) that’s an offshoot of the better-known cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). A principal aim of ACT is to develop psychological flexibility – which will help you thrive at university (and in life in general).” These contain two elements:

- Figure out what’s important to you.

- Identify your values

- Set some specific goals, preferably SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound) goals

- Recognise the barriers in your way and use mental techniques to overcome your barriers

- Figure out how to interact with your thoughts and feelings so that they don’t stop you from moving towards what’s important to you.

- Difficult feelings are normal – it’s how you respond to them that matters

- Develop your ‘willingness’

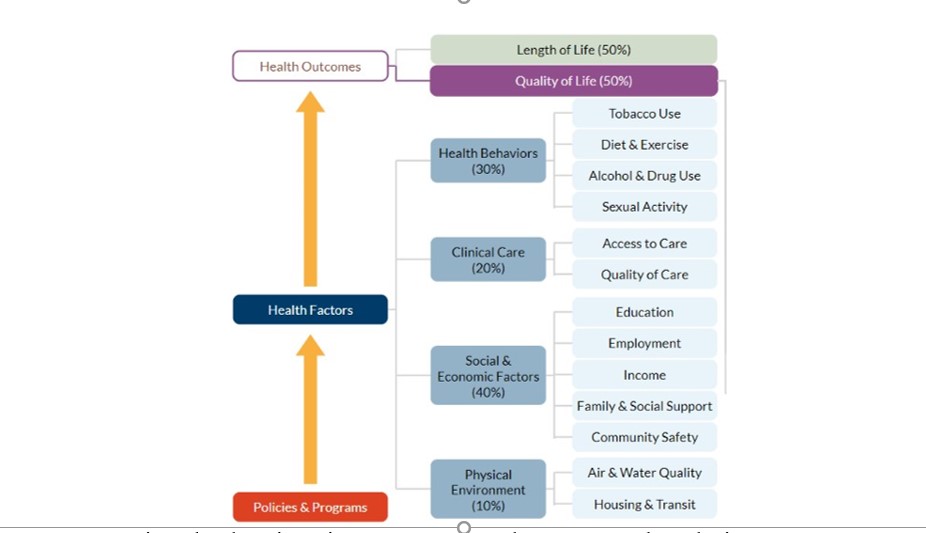

Factors Affecting Length and Quality of Life

The length of life and the quality of life are the basic yardsticks of well-being. Length of life is dependent on somewhat measurable factors. Quality of life is not so easily measured. Taking both together, a US study estimated the weightage of various factors. Social and economic factors account for 40% and health behaviours account for 30%. This is where our efforts and interventions should lie, then 70% of the factors of well-being will be covered. Clinical care, physical and mental, only accounts for 20%, though huge investments of money, academic and human resources are invested here.

Recommendations

Balance of life for students in MLCU

- Academics

- A friendly, stress-free and supportive learning environment

- Community and experiential learning

- Emphasis on careers and livelihood

- Focus on individuals, rather than cohort

- Courses on altruism, social activism, happiness and well-being

- Personal development and care

- Physical-psycho-social profile at the time of admission

- Career counselling

- Opportunities for a wide array of extra-curricular activities including on the weekends

- Life skills, decision-making and self-care coaching

- Health and campus safety

Balance of life for faculty and staff in MLCU

- Professional

- Academic development opportunities

- Individual career management support

- Consideration of preferred academic tracks for performance evaluation based on individual personal statements

- Personal and family

- Gender-sensitive policies

- Family support such as creche, extra consideration for single parents

- Assistance with personal and long-term finance planning

- Health and life insurance

Steps so far

- Presentation and initiation of discussion on well-being by Dr Gideon Arulmani at the University Retreat on Aug 2, 2022.

- Conceptualization of the pyramid scheme for student well-being by Dr Gideon and the offices of Dean, Academics and Dean, Students

- Career Development Workshops for MLCU faculty and staff conducted on Nov 24-25, 2022 and Mar 28-29, 2023

- Advanced Skills for Counselling conducted by Dr Gideon on Mar 29-31, 2023

- Workshop on Faculty Well-being on May 2-3, 2023 by Dr Suhas Chandra and Dr Denis Xavier, from St Johns Medical College, Bangalore

References

R P Auerbach et al. Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol Med. 2016;46(14):2955-2970. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716001665. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27484622/

Work-life balance: what really makes us happy might surprise you. Lis Ku, Senior Lecturer in Psychology, De Montfort University (2021). The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/work-life-balance-what-really-makes-us-happy-might-surprise-you-168446

A Psychologically Rich Life: Beyond Happiness and Meaning. Shigehiro Oishi and Erin C. Westgate. Psychological Review (2021): 129(4), 790–811. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000317 https://www.erinwestgate.com/uploads/7/6/4/1/7641726/oishi.westgate.psychrev.2021.pdf

Catherine Gewertz (2021). Teachers’ Mental Health Has Suffered in the Pandemic. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/teachers-mental-health-has-suffered-in-the-pandemic-heres-how-districts-can-help/2021/05

Madeline Will (2021). Teachers Are More Likely to Experience Depression Symptoms Than Other Adults. Education Week.

https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/teachers-are-more-likely-to-experience-depression-symptoms-than-other-adults/2021/06

Michelle B. Riba, and Preeti N. Malani (2022). Mental Health on College Campuses: Supporting Faculty and Staff. Psychiatric Times. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/mental-health-on-college-campuses-supporting-faculty-and-staff

Nic Hooper (2023). How to make the most of university. Psyche. https://psyche.co/guides/how-to-thrive-at-university-by-learning-psychological-flexibility?utm_source=Psyche+Magazine&utm_campaign=155bbbbeef-

Alexus McLeodis (2023). Chinese philosophy has long known that mental health is communal. https://psyche.co/ideas/chinese-philosophy-has-long-known-that-mental-health-is-communal?utm_source=Psyche+Magazine&utm_campaign=a9a3bdf830-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2023_03_13_09_21&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_-a9a3bdf830-%5BLIST_EMAIL_ID%5D

William E. Copeland et al (2020). Associations of Despair With Suicidality and Substance Misuse

Among Young Adults. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(6):e208627. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8627

Carol Graham (2021). America’s crisis of despair: A federal task force for economic recovery and societal well-being. The Brookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/research/americas-crisis-of-despair-a-federal-task-force-for-economic-recovery-and-societal-well-being/

Sterling P, Platt ML. Why Deaths of Despair Are Increasing in the US and Not Other Industrial Nations-Insights From Neuroscience and Anthropology. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022 Apr 1;79(4):368-374. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.4209. PMID: 35107578.

Melissa Daimler (2018). Why Great Employees Leave “Great Cultures”. Harvard Business Review. May 11, 2018

Paul B. Lester, Ed Diener, and Martin Seligman (2022). Top Performers Have a Superpower: Happiness

MITSloan Management Review, February 16, 2022.

R Golani and R Narayanan (2023). Discrimination in the IITs is something to write about. The Hindu Mar 22, 2023.